Media Contacts:

Timothy Pierce: tpie gwu [dot] edu (tpie[at]gwu[dot]edu), 202-994-5647

gwu [dot] edu (tpie[at]gwu[dot]edu), 202-994-5647

GW Media: gwmedia gwu [dot] edu (gwmedia[at]gwu[dot]edu), 202-994-6460

gwu [dot] edu (gwmedia[at]gwu[dot]edu), 202-994-6460

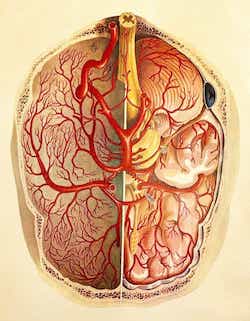

WASHINGTON (May 6, 2021) — The cerebellum — a part of the brain once recognized mainly for its role in coordinating movement — underwent evolutionary changes that may have contributed to human culture, language and tool use. This new finding appears in a study led by Elaine Guevara, a former postdoctoral scientist in the Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology at the George Washington University and current assistant research professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University.

Scientists studying how humans evolved their remarkable capacity to think and learn have frequently focused on the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain vital for executive functions, like moral reasoning and decision-making. But recently, the cerebellum has begun receiving more attention for its role in human cognition. Guevara and her team investigated the evolution of the cerebellum and the prefrontal cortex by looking for molecular differences between humans, chimpanzees and rhesus macaque monkeys. Specifically, they examined genomes from the two types of brain tissue in the three species to find epigenetic differences. These are modifications that do not change the DNA sequence but can affect which genes are turned on and off and can be inherited by future generations.

“Our genome is quite similar to the genomes other primates, but differences in which genes are turned on where during development partly accounts for the vast differences in anatomy and biochemistry we see among species,” Guevara, who conducted the research while at GW, said. “Epigenetic modifications offer something of a record of which genes were turned on during development and as a result can offer clues to the origins of species differences, including in the brain. To better understand what sets humans apart from other species cognitively, we looked for places in the genome with unique methylation in humans compared to chimpanzees and rhesus macaque monkeys in two parts of the brain, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the lateral cerebellum.”

Compared to chimpanzees and rhesus macaques, humans showed greater epigenetic differences in the cerebellum than the prefrontal cortex, highlighting the importance of the cerebellum in human brain evolution. The epigenetic differences were especially apparent on genes involved in brain development, brain inflammation, fat metabolism and synaptic plasticity — the strengthening or weakening of connections between neurons depending on how often they are used.

The epigenetic differences identified in the new study are relevant for understanding how the human brain functions and its ability to adapt and make new connections. These epigenetic differences may also be involved in aging and disease. Previous studies have shown that epigenetic differences between humans and chimpanzees in the prefrontal cortex are associated with genes involved in psychiatric conditions and neurodegeneration. Overall, the new study affirms the importance of including the cerebellum when studying human brain evolution.

“Because the cerebellum is associated with controlling movement in all vertebrates, it has not traditionally attracted as much attention in the quest to understand what is behind humans’ cognitive prowess,” Guevara said. “However, the cerebellum is home to most of the brain’s neurons and processes tons of information coming in from the cerebral cortex. It makes sense that it would be coopted during human evolution into supporting the complex execution of sophisticated, learned behaviors.”

The study, “Comparative analysis reveals distinctive epigenetic features of the human cerebellum” published May 6th in the journal PLOS Genetics.

-GW-