MEDIA CONTACTS:

Matt Wood (UChicago): mwood2 uchicago [dot] edu, 773-702-5894

uchicago [dot] edu, 773-702-5894

uchicago [dot] edu, 773-702-5894

uchicago [dot] edu, 773-702-5894Maralee Csellar: csellar gwu [dot] edu, 202-994-7564

gwu [dot] edu, 202-994-7564

gwu [dot] edu, 202-994-7564

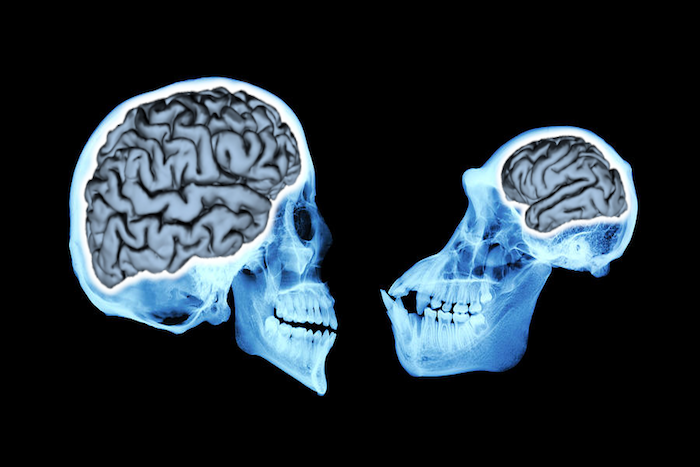

gwu [dot] edu, 202-994-7564Modern humans have brains that are more than three times larger than our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos. Scientists don’t agree on when and how this dramatic increase took place, but new analysis of 94 hominin fossils shows that average brain size increased gradually and consistently over the past three million years.

The research, published this week in The Proceedings of the Royal Society B, shows that the trend was caused primarily by evolution of larger brains within populations of individual species, but the introduction of new, larger-brained species and extinction of smaller-brained ones also played a part.

“Brain size is one of the most obvious traits that makes us human. It’s related to cultural complexity, language, tool making and all these other things that make us unique,” said Andrew Du, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Chicago and first author of the study. “The earliest hominins had brain sizes like chimpanzees, and they have increased dramatically since then. So, it’s important to understand how we got here.”

Du began the work as a graduate student at the George Washington University. His advisor, Bernard Wood, GW’s University Professor of Human Origins and senior author of the study, gave his students an open-ended assignment to understand how brain size evolved through time. Du and his fellow students, who are also co-authors on the paper, continued working on this question during his time at George Washington, forming the basis of the new study.

“Think about the entrance to a building. You can reach the front door by walking up a ramp, or you can take the steps. The conventional wisdom was that our large brains had evolved because of a series of step-like increases each one making our ancestors smarter. Not surprisingly the reality is more complex, with no clear link between brain size and behavior.”

“The moral is this - when you don’t understand something ask a bunch of bright and motivated students to figure it out”

Du and his colleagues compared published research data on the skull volumes of 94 fossil specimens from 13 different species, beginning with the earliest unambiguous human ancestors, Australopithecus, from 3.2 million years ago to pre-modern species, including Homo erectus, from 500,000 years ago when brain size began to overlap with that of modern-day humans.

The researchers saw that when the species were counted at the clade level, or groups descending from a common ancestor, the average brain size increased gradually over three million years. Looking more closely, the increase was driven by three different factors, primarily evolution of larger brain sizes within individual species populations, but also by the addition of new, larger-brained species and extinction of smaller-brained ones. The team also found that the rate of brain size evolution within hominin lineages was much slower than how it operates today, although why this discrepancy exists is still an open question.

The study quantifies for the first time when and by how much each of these factors contributes to the clade-level pattern. Du said he likens it to how a football coach might build a roster of bigger, strong players. One way would be to make all the players hit the weight room to bulk up. But the coach could also recruit new, larger players and cut the smallest ones.

“That’s exactly what we see going on in brain size,” he said. “The dominant process is like the players hitting the gym. They’re evolving larger brains within a population. But we also see speciation events adding larger-brained daughter species, or recruiting bigger players, and we see extinction, or cutting the smallest players too.”

The study, “Pattern and process in hominin brain size evolution are scale-dependent,” was supported by the National Science Foundation. Additional authors include Andrew M. Zipkin from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the George Washington University (GW); Kevin G. Hatala from Chatham University and GW; Elizabeth Renner from the University of Stirling, Scotland and GW; Jennifer L. Baker from the Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institute of Health and GW; and Serena Bianchi and Kallista H. Bernal from GW.

-GW-